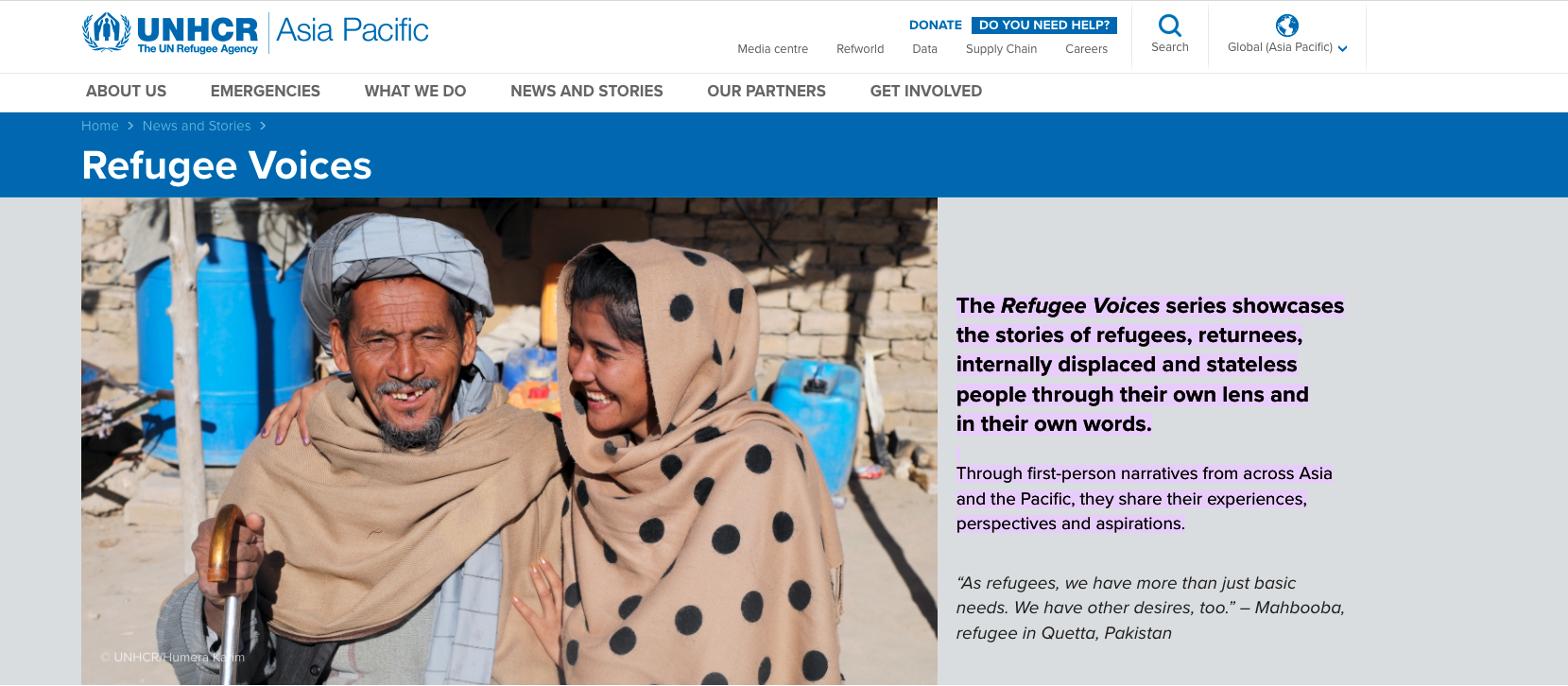

Introduction The representation of refugees in mainstream media has long been object of intense debate. In particular, media outlets are criticised for promoting certain ‘standard’ narratives which do not represent refugee experiences in their plurality and complexity. Instead, mainstream media resort to ‘prefabricated’ paradigms to match public expectations. However, by doing so they risk reducing and simplifying the refugee experience. There are two problematic narratives which mainstream media often resort to: the excessive victimhood narrative, and the silencing of refugee voices. Why it matters How mainstream media talk about refugeehood matters for two reasons. Firstly, how we represent reality has an impact on how we understand and act inside our lived realities. Secondly, depriving refugees of being rightfully represented neglects their fundamental needs of social identity and understanding (Acha, 2015). Representation matters Our society is characterised by deep communication imbalances. Some groups, such as the mainstream media, hold the power to authoritatively talk about others. By deciding what is being talked about, for how long and in what terms, mainstream media therefore can exercise the power to ‘set the agenda’ of conversation. Such power is especially important in our current society, based as it is on an ‘attention economy’ (Simon, 1971), or an ‘economy of visibility’ (Banet-Weiser, 2015) where quantity overweighs quality. This stands in stark contrast with marginalised groups, which only seldom have the opportunity to publicly talk about their experiences, and often end up silenced. Crucially, such agenda-setting power does not only matter in the ‘abstract’ realm of the media and culture. Media representations matter in the physical world as well. As anthropology luminary Edward Said argued (1994), culture is tightly intertwined with political power. The power to frame a conversation contributes to producing certain worldviews, which people will then act on. Therefore, how the media represent and frame refugee experiences is of great relevance: it can shape what the public knows about refugees, and ultimately influence their opinions and actions. The human needs for understanding and identity Second, as highlighted by Dr. Kenneth Acha, the needs for understanding and social identity are part of the fundamental human needs. If the media repeatedly circulate an essentialised image of refugeehood, refugees will neither feel understood nor recognise themselves within those narratives. This raises important concerns, as Acha comments: ‘When one’s identity is considered inferior, illegitimate, or threatened by others in some way, identity issues arise’. Problematic narrative #1: Refugee victimhood A tradition of representing refugees as helpless victims marks mainstream media. Anthropologist Liisa Malkki (1996) famously argued that refugees are excessively victimised in dominant discourse, becoming ‘pure victims’ who are ‘defined by their needs’. While promoting caring attitudes towards refugees is certainly a positive endeavour, we ought to be careful about portraying realistic stories. Portraying refugees merely as symbols of suffering and compassion will not further our understanding of refugee experiences, which are complex, diverse and multifaceted. Take, for example, the case of refugee and PhD student Rifaie Tammas. In his article on OpenDemocracy (2019), Tammas strongly criticises the interview he underwent with a prominent media outlet. The journalists, he comments, were not really interested in understanding his experience and research. Instead, they merely focused on his personal past and on the moments where he appeared the most vulnerable. If the media continue to over-victimise refugees, focusing only on the emotional aspects of their stories, Tammas warns, they will ‘do more harm than good’. Responding to this concern, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has therefore declared that institutions need to be particularly careful about sharing painful details of refugee stories. As there is often a power imbalance between refugees and media outlets, the UNHCR has recommended to pay attention to refugees’ right to determine how and when they share their stories. The question of voice Another issue with refugee representation is that refugees are often silenced in the media. Indeed, it is rare to see refugees who ‘self-represent’ by sharing their own experiences and opinions. Many studies have explored refugee voices in the media, concluding that they are often marginalised and silenced. For example, media studies professors Lilie Chouliaraki and Rafal Zaborowski carried out a study of the 2015 refugee crisis media coverage, comparing coverage in eight European countries. The aim of the study was to establish whether and how refugees speak in the news. They concluded that how voice was distributed in the examined news followed a strict hierarchy, one which prioritised certain ‘Western’ actors over refugee voices. Who is it, then, that speaks on behalf of refugee subjects? According to professor Myria Georgiou (2018) from the London School of Economics, mainstream newspapers rely on ‘expert’ figures. These figures, often Western, are elected to speak about the refugee issue and to explain it to the public. Problematically, by doing so ‘experts’ take up the space of refugee voices, thus effectively ‘silencing’ them in the media. A practical example of this is raised in a study by WACC Europe and the Churches Commission for Migrants in Europe (2017, see Picture 1). Their study broke down who gets to speak in newspapers across different countries. It concluded that only in 22% of the sampled articles did migrants speak about their personal experience. Moreover, only in 3% of the articles did migrants act as commentators or experts on the refugee condition. In the vast majority of cases, migrants were only spoken about. Although this study involved the broader category of migrants, instances of refugee silencing work similarly. Refugees are often ‘out-quoted’ by figures such as politicians, who are seen as more authoritative about refugee status (WACC 2017). These dynamics mean that refugees are turned into ‘speechless emissaries’, to use Liisa Malkki’s term (1996). Challenging the narrative Within a media ecology which systematically silences and victimises refugee voices, what can be done to challenge dominant discourse? Due to a sensibilisation to the problematic aspects of refugee representation in the last years, new initiatives are developing. The aim is create new and better ways to tell refugee stories to the public. Refugee resilience A suitable approach involves focusing on refugee resilience rather than victimhood. For example, the ‘I am an Immigrant Campaign’ in the U.K. adopted this approach. In the campaign (see Picture 2), refugees are portrayed as active, agentic individuals who also contribute to the country’s economy in a variety of ways (e.g., as mental health nurses, customer service assistants, bus drivers…). Nevertheless, media outlets should be careful to overplay refugee resilience: after all, refugee experiences are often devastating, and that aspect should not be completely neglected. Voice Similarly, a project by the UNHCR sought to challenge the silencing of refugee voices. The ‘Refugee Voices’ project focuses on first-person narratives of refugees. In these stories, refugees are free to self-represent by recounting their experiences’. In the words of the High Commissioner: ‘The Refugee Voices series showcases the stories of refugees, returnees, internally displaced and stateless people through their own lens and in their own words. Through first-person narratives from across Asia and the Pacific, they share their experiences, perspectives and aspirations’ Both projects attempt to challenge problematic refugee narratives by proposing new ways to speak with, rather than about, refugees. As a result, both experiences end up being more inclusive and let refugees play a part in constructing their own social identity.

Conclusion While the over-victimisation and silencing of refugee voices might still be around in mainstream media, it is important to spark dialogue about how representational transformation can be achieved. As argued above, the way in which refugees are represented in the media can have crucial repercussions on our reality. Firstly, promoting positive, diverse narratives of refugeehood can influence people’s worldviews and actions. Secondly, it can help sustain the fundamental human needs of understanding and social identity. Thus, by proposing new narratives which listen to refugee voices, these projects subvert the problematic narratives of refugeehood. Works cited Articles and reports Acha, K. (7 Jul 2015). ‘The 7 Fundamental Human Needs’. Kenneth Acha Ministries: Loving People, Shaping Destiny. Available at: https://www.kennethmd.com/the-7-fundamental-human-needs/ [accessed 23 Mar 2022]. Banet-Weiser, S. (2015). Keynote Address: Media, Markets, Gender: Economies of Visibility in a Neoliberal Moment. The Communication Review 18:1, 53-70. DOI: 10.1080/10714421.2015.996398 Chouliaraki L, Zaborowski R. (2017). ‘Voice and community in the 2015 refugee crisis: A content analysis of news coverage in eight European countries.’ International Communication Gazette. 79 (6-7), 613-635. DOI:10.1177/1748048517727173 Churches Commission for Migrants in Europe and WACC Europe. (Nov 2017). ‘Changing The Narrative: Media Representation Of Refugees And Migrants In Europe’. Available at: https://www.refugeesreporting.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Changing_the_Narrative_Media_Representation_of_Refugees_and_Migrants_in_Europe.pdf [accessed 24 Mar 2022]. Georgiou, M. (2018). ‘Does The Subaltern Speak? Migrant Voices In Digital Europe. Popular Communication: Connected Migrants 16 (1), 45-57. Simon, H. A. (1971). Designing Organizations for an Information-rich World. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 37-52. Archived from the original on 6 October 2020. Tammas, R. (1 Nov 2019). ‘Refugees Stories Could do More Harm than Good’. openDemocracy. Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/refugee- stories-could-do-more-harm-good/ [accessed 23 Mar 2022]. UNHCR (n.d.) ‘Refugee Voices’. UNHCHR website. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/asia/refugee-voices.html [accessed 23 Mar 2022]. Pictures Picture 1. Churches Commission for Migrants in Europe and WACC Europe. (Nov 2017). ‘Changing The Narrative: Media Representation Of Refugees And Migrants In Europe’. Available at: https://www.refugeesreporting.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Changing_the_Narrative_Media_Representation_of_Refugees_and_Migrants_in_Europe.pdf [accessed 23 Mar 2022]. Picture 2. Millin, S. ‘I am an immigrant’. (Almost) Infinite ELT Ideas. WordPress article. Available at: https://infiniteeltideas.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/8xposters.jpg [accessed 24 Mar 2022]. Picture 3. News and Stories: Refugee Voices. UNHCR website. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/asia/refugee-voices.html#:~:text=The%20Refugee%20Voices%20series%20showcases,their%20experiences%2C%20perspectives%20and%20aspirations [accessed 24 Mar 2022].

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Author

Francesca is a DPhil student at Oxford University. She researched and wrote this article as part of the Oxford University Micro Internship programme.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed